Quoting a Bible Verse

Seraphs were in attendance above him; each had six wings: with two they covered their faces, and with two they covered their feet, and with two they flew.

Isaiah 6:1-8; Luke 5:1-11

This is a vision or a dream. A dream Isaiah is said to have had about his purpose as a prophet. And yet Isaiah in the dream questions his worthiness for the task. “Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips; yet my eyes have seen the King, the LORD of hosts!”

He has seen God but does not know what to do next. But the dream does not release him from his responsibilities.

Then one of the seraphs flew to me, holding a live coal that had been taken from the altar with a pair of tongs. The seraph touched my mouth with it and said: “Now that this has touched your lips, your guilt has departed and your sin is blotted out.”

The story acknowledges that even a prophet can be sinful. Someone worthy to profess the expectations of God can be well shy of perfect. And so Isaiah went forth and spoke for God.

The Gospel reading was quite similar. Jesus comes upon fishermen and their boat. Jesus asks the men to borrow their boat so he can speak to people from out on the water. Perhaps it was easier to be heard while not being crowded. Afterwards, Jesus has them pull further out into deeper waters to fish, even though they have had little luck that day. They cast their nets and pull up so many fish that another boat must come to help them.

Simon, later known as Peter, falls to his knees on the shore and says “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!” Very much like Isaiah, Peter feels he is unworthy to follow: unworthy, incapable, sinful. Jesus does not care. He simply asks for Peter and the rest to follow.

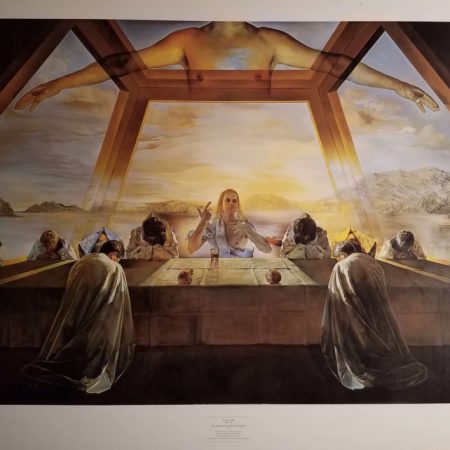

This morning we have another painting. The artist is Salvador Dali, a 20th century Spanish artist. When I first saw this image, I thought there must have been a mistake. Dali painted floppy watches. Dali made sculptures out of telephones and lobsters. This painting was religious. It was actually reverent. It seemed inconsistent with my preconceptions of Salvador Dali.

Let’s take a look. This is a composite scene arranged around the central story of the last supper. I am told that the actual painting gives off a strong luminescence, a sun-like halo surrounding the central figure of Jesus. Note the other figures bent over around the table in prayer. We cannot see who they are. Which one is Peter, the reluctant follower? Who is Judas, the betrayer? John or James, Thomas or Andrew? Who is young, who is old? Who is solid in faith and who hides doubt behind praying hands?

Surrounding the figures is a geometric shape, a portion of a dodecahedron of gold and glass. Dodecahedrons have twelve sides, by the way, and the lines of the painting are based upon the golden mean, a balanced mathematical proportion used in art and architecture. In the background, there is a body of water and a few boats. Is this the Sea of Galilee? The landscape also is similar to the seaside in Dali’s home province of Catalonia.

Jesus’ hand is raised as if to make a point, gesturing toward that higher disembodied figure with outstretched arms – outstretched to the world or outstretched in reference to the crucifixion. Also notice something is missing. The figure above is entirely transparent in the center, on the chest where the heart would be.

Dali came back to Catholicism later in life, probably after he fled the war in Europe and came to the U.S. He no doubt grew up surrounded by Catholic religious imagery. Imagery of the sacred heart of Jesus, a form of religious devotion to his humanity and the love and compassion embodied in his heart. I wonder why the heart has gone missing in this painting. Perhaps the larger image is not intended to represent Jesus at all, but God. God whose heart could be said to have been sent down into the world, a reference to the incarnation of God in the person of Jesus.

Dali was a key figure in the surrealist movement, although he was ejected from that loose conclave of artists. A little history is needed to understand why.

Art is often used as a way to interpret the world and events around us. The First World War exacted a staggering human toll. And that long shadow of death and suffering transformed the world. Old empires were broken up, new nations were born. Marxism became a new philosophical force after the Russian Revolution in 1917. And fascism began to grow in response.

Artists were influenced by these various events. One artistic movement, Dadaism, arose as a reaction to the horrors of the First World War. This movement rejected reason and logic and instead embraced nonsense and irrationality. Dadaism mocked artistic and social conventions, instead emphasizing the illogical and the absurd in the arts.

And from this one movement was born another, known as surrealism. It was a movement in art seeking to express the subconscious mind. Its aim was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality”. Super-reality, that which is beyond reality, or the sur-real.

There is no bright line between these two movements, Dadaism and surrealism. How would you draw a line between the illogical and the subconscious? Between that which is absurd and that which is a dream?

Salvador Dali was an early surrealist. But within that group of cultural outsiders, Dali did not find an easy place. One reason for this was that Dali refused to become political with his work. Many surrealists were anarchists, Marxists, or Communists. Their art was often designed to respond to the perceived weaknesses and failures of traditional society. Dali once described himself as an anarchist and a monarchist. Those are not compatible ways of thinking, which is probably why Dali said so in the first place.

I mentioned that Dali was kicked out of the surrealist fold. The others thought he was a surrealist in it just for the money, just for the fame. Call him the first sell out. Dali was kicked out of the surrealist club, so to speak, but then most of the surrealists were kicked out of communist circles, so there’s karma for you.

Dali came to the conclusion that he was surrealism, that he embodied it rather than participated in it. That was a rather grandiose self-reflection. And by representing the whole artistic movement, he could also declare that surrealism itself could be apolitical.

And this got me wondering. Wondering about art and history, music and writing, and -bdare I say it – religion and culture. I was wondering if any of those facets of a society can be completely apolitical. Not a player in the great game of the possible otherwise known as politics. Can they be? Should they be? Is anything ever devoid of politics? And where does that leave a good New Englander long schooled in techniques for avoiding talking about politics, money, and religion?

One does not talk about them in polite company. And yet aren’t they important subjects? Don’t they matter? And if they are important and if they do matter, what is so impolite about discussing them? Perhaps it is not a question of the topics being impolite. Instead, it may be a question of never having learned how to talk about those topics without the people involved becoming impolite.

Talking about money as more than crass self-interest. Speaking of politics as more than a contentious desire to win at all costs. And religion. Having a discussion about religion, religion as being more than a source of personal comfort divorced from the challenges of the world and the needs of others.

I stumbled across an article critical of Dali. Not critical of his art, but critical of him as a person. He has many critics, but I remarked upon this one because it was the author George Orwell. Orwell who famously wrote Animal Farm and 1984 as critiques of totalitarianism. Orwell in these books criticized extremes of the political spectrum in equal measure – apolitically as to right versus left, but quite political as to the risks and dangers of either form of extremism.

In this article, Orwell was responding to an autobiography by Dali, which the former found rather disappointing. Orwell thought it was intellectually dishonest to write a flattering autobiography because the author, of all people, truly knew the hidden sins of a life. To leave those out, to gloss those over, was arrogance and vanity. Dali was neither Isaiah nor Peter confessing their unworthiness.

And while Orwell conceded that Dali had talent, he found the artist otherwise lacking. He wrote, “The two qualities that Dali unquestionably possesses are a gift for drawing and an atrocious egoism…. One ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dali is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being.” Orwell also found Dali’s rediscovery of religion to be unrealistic, even contrived. He said, “You could even top it all up with religious conversion, moving at one hop and without a shadow of repentance from the fashionable salons of Paris to Abraham’s bosom.”

The return to religion was suspect for Orwell because Dali’s art was dependent upon transcending such traditions. As Orwell described Dali’s surrealism, “There is always one escape: into wickedness. Always do the thing that will shock and wound people.” But you cannot shock unless there is a line to be crossed. You cannot wound if the audience is immune to your weapon of choice.

Dali was not a pious man. He lived the life of a performer as much as an artist. And as a show man, he sought to entertain. Honestly, in comparison to some of the other artists I have reviewed in this series, Dali was not particularly shocking in his behavior. He had some strange habits and predilections, which I will spare you. But he was a duffer amidst the likes of Paul Gauguin or even Pablo Picasso. A bush league sinner even as he tried to play up his eccentricities. George Orwell’s criticism of Dali always loops back to the same issues: Dali was egotistical and selfish. It was all about him – look at me, look at me. But that is pretty garden variety sinning in my professional experience.

The more interesting criticism would be, for lack of a better term, artistic cowardice. Dali lived in Spain during the civil war there, but never chose a side. This was a life and death struggle for the survival of his homeland, and yet he kept finding a way to avoid becoming embroiled on either side. This is how Orwell described Dali’s avoidance of taking a side:

The first thing that we demand of a wall is that it shall stand up. If it stands up, it is a good wall, and the question of what purpose it serves is separable from that. And yet even the best wall in the world deserves to be pulled down if it surrounds a concentration camp.

In the same way it should be possible to say, ‘This is a good book or a good picture, and it ought to be burned by the public hangman.’ Unless one can say that, at least in imagination, one is shirking the implications of the fact that an artist is also a citizen and a human being.

Orwell expects art to take a side, to engage with the issues of the day. Maybe that is not choosing a political party. Probably it is not joining the propaganda team of one side of a conflict versus another. Perhaps this is not being political at all, but taking sides in a moral conversation. Of casting off the labels and branding for a moment and declaring that somethings are right and others are wrong. And yet a desire to avoid a so-called political debate can become mired in this sort of talk.

A few months ago, this church took a stand on a moral issue. We drafted a letter decrying the separation of families seeking entry along the southern U.S. border with Mexico. Children being taken away from their parents because their parents were to be charged with the alleged crime of entering the United States in a certain manner. That letter was sent out to elected officials in Boston and Washington.

Let me ask you a question – was that being political? Almost anything in the current political climate can be sorted along political lines, potentially rendering it an unfit topic for discussion. Discussion in polite conversations, wherever those happen to occur these days.

I am in a weird position here. I think I have been pretty good about avoiding overt politics in the pulpit. I have never said vote for X rather than Y, this party versus that one. Actually, I do not recall ever mentioning the name of a sitting president. Conversely, I have not shied away from moral issues and that can get murky for some. But where is that line to be drawn?

A few years ago, in response to a concern that something I had preached was too political, I said something along these lines: if it is in the book, I get to talk about it. What book, might you ask? The Bible. If it is in the Bible, not only can I talk about it, I am duty bound to do so.

And there is a lot in that book. A lot I rarely talk about. There is a good bit about sex. Some of it obscure, some of it obvious, much of it way out of date. Out of date not because the Bible has expired, but because the way modern followers of Jesus consider the Bible has changed. And that does not mean they stopped following.

There is a lot in the Bible about money. It is a sin to charge interest, so bankers and brokers beware. Rich people cannot go to heaven, so sell everything you own and give it to the poor. How’s that one working out?

And politics. That is an interesting question, because in some countries the Bible is used to push a political agenda while in others it is the standing tradition to render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. Let the princes rule and let the church keep silent.

For all the shock value of his work, Dali ironically spent most of his life avoiding political controversy and yet cozying up to people in power. The supposed anarchist and former communist was granted the title of the First Marquis of Dali de Pubol. He became an aristocrat. I am not sure that this means anything. But for a man who called himself an anarchist and a monarchist, he seemed to be leaning a bit more in one direction versus the other. And by the way, the last drawing Dali ever made he personally handed to King Juan Carlos of Spain, who was visiting Dali on his death bed.

America is in a peculiar moment in its political history. Mainline churches generally followed the maxim that there should be a separation between church and state. There are arguments about prayer in schools or, heaven forbid, sex education, but otherwise generally hands off. Others did not get that particular memo, so some religious groups have tried to influence the political activities of members of their congregations.

I have no desire to do that. Vote for whom ever you want. My job is not to look over your shoulder to make certain the right ballot boxes have been checked. But if it is in the book, I get to talk about it, I get to preach about it, I get to write about it. I get to present the moral issues of the day.

War and peace are in the book. Immigration and refugees are in the book. Gays and lesbians are in the book. Slavery and freedom, money and sex, culture and politics – all in the book. One of the reasons these topics are not always discussed in church is that these topics might make those gathered uncomfortable. Views might vary from person to person. And this can be a concern.

I cannot pretend to be able to speak for every minister in every pulpit about these matters. But here we are in a particular community of people gathered with purpose. And more so than that, we are Unitarians. That means many things to many people, but one point of agreement is that Unitarians do not require one another to adopt a common creed. No detailed list of articles of faith, no bright line tests to delineate who is in the fold and who is on the outs. That is basic Unitarianism.

How one manages living without a religious rule book can seem like a challenge. But I once described being a Unitarian this way – we do not concern ourselves with what you believe, but with what you do. What you do. This is how to embrace the difficult tasks of life while gathering in a community of people with potentially diverse beliefs. Like Isaiah in his dream, it does not matter if you do not feel worthy. Like Peter on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, it does not matter if you consider yourself too sinful or too broken or too unprepared.

The ultimate goal for any Unitarian is to learn to be together, to accept one another as we are now, each as worthy and with dignity. And from that simple assumption, each worthy of love and worthy of respect, how we work together will unfold. An implicit rule becomes an explicit way of living, much like the subconscious being revealed. But it does not stop there, not within these four walls. That sense of worthiness keeps going, each and every one of us. And with worth must come respect and with respect should follow patience. Should follow.

This community looks to the lessons of Jesus and the teachings of the Bible as ancient ideas leading to a good life. Yes, you can avoid some of those ideas because they are not easy matters to discuss. Certainly, you can skip over some hard topics, as if to edit them out of a book. But they are there. The hard topics are there. The moral quandaries and human failings are still there.

And like in the dream of Isaiah, we are not being let go. Like the protestations of Peter, we are still expected to take up the challenge. That book can be a pest with its many expectations and exhortations. But if we care about that book, we cannot turn away. And if we hear it from the book, we need to be ready to speak about it from the heart. To go forth and maybe even to speak. To speak, as if for God. Amen.

0 Comments